On the use of Aleatoricism in 'Magnificat'

- peter-relph

- Nov 17, 2021

- 4 min read

I'm delighted to announce that my Magnificat will be released on Dr James Jordan and The Westminster Williamson Voices' upcoming Christmas CD A Scattered Light In Winter later this week.

In 2019 I completed a setting of The Magnificat, a biblical text where Mary is talking to her cousin Elizabeth. In this setting I incorporated aleatoric sections - sections where the creation of sound is somehow left to chance - into the music.

When using aleatoric elements in music, you inevitably run the risk of creating what Judith Weir memorably described as ‘Aural Porridge’ - where a cacophony of different voices makes words indecipherable.[1] In a liturgical context, where sung words are often important to a service, this can be a problem.

Many composers who have used aleatoric elements music have tended to do so for specific reasons. Jonathan Harvey’s Come, Holy Ghost, for example, grows from a simple statement of the plainsong Veni Sancte Spiritus with harmonic drone into complex aleatoric melodic fragments derived from fragments of the material. [2] This resonates with the idea of the coming of the holy ghost speaking in many tongues.

Richard Causton’s Christmas carol Flight progresses from monody to the whole choir engaged in singing phrases independently and the trebles instructed to sound like sirens, before returning to homophony at the end of the piece.[3] This use of chaotic aleatoric writing is intended to resonate with the many voices of refugees during the 2015 refugee crisis.

With Magnificat, I began by looking at the themes in the text. The joyous nature of Mary’s speech made me investigate other forms of happiness, and I came upon the four levels of happiness defined by Spitzer, based upon the writings of Aristotle.[4]

1. The first is the happiness from material objects, called ‘External-Pleasure-Material’. This level of happiness is about sensual gratification based on things.

2. The second is ego gratification, called ‘Ego-Comparative’. This is happiness from comparison: being better, or being more admired than others.

3. The third, ‘Contributive-Empathetic’, is the happiness from doing good for others and making the world a better place. This is based on the human desire for connection, goodness, meaning, compassion, friendship and unity.

4. The fourth and final level, called ‘Transcendent’, is finding a balance between the other levels.

The first two levels therefore, deal purely with the self and the second two focus on concern for others. These ‘four levels’ came to form the basis of the structure of the piece. In the table below I show how each of the levels affect each section of the piece (and text).

As the text itself lay at the heart of my approach to the creation of this composition, its audibility was of considerable importance. The main body of the text of the Magnificat has been set in a simple melody over a drone in the first two sections.

The two melodies in these sections are then overlaid in section three, with alternating melodies between the soloist and the sopranos. The shift from one singer singing the text in the first two sections to many in sections three and four evokes Spitzer’s levels of happiness, where the first two are concerned with the self and the second two are with others.

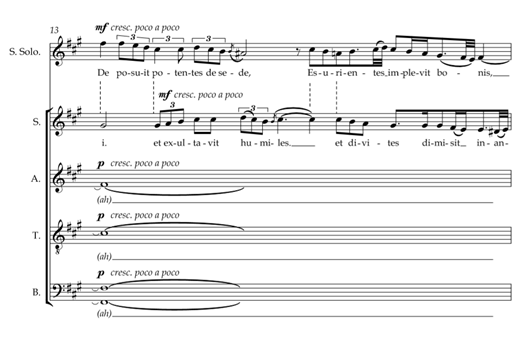

Interplay between melodic lines in section 3 in ‘Magnificat’ (bar 13)

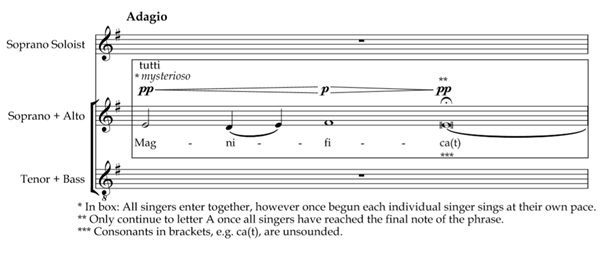

Whilst audibility of the text is of premier importance in Magnificat, aleatoric elements have been used to further reinforce the musical structure. Aleatoric sections based around the word ‘Magnificat’ occur at the beginning of the piece and at transitions between each of the sections of the piece. The purpose of aleatoricism in Magnificat is to further reinforce the musical structure.

Singers are instructed to perform statements of the word ‘Magnificat’ at their own speed, the music only progressing once all singers have completed their line. As the piece progresses the number of parts singing in these sections gradually increases, from Sopranos and Altos singing a single melodic fragment at the beginning to the full choir singing different melodies at the end of Section 3.

Aleatoric vocal writing in ‘Magnificat’ (bar 1)

There is a gradual increase in the number of different melodic lines, making the harmony in these sections gradually become richer as the piece progresses. This further reinforces each of Spitzer’s levels of happiness, from concern with the self - one melody and few voices, to concern for others - harmony and many voices.

I hope you enjoy the new CD - have a listen when it comes out on Friday - and do consider buying a physical copy. My sincere thanks to Dr James Jordan and The Westminster Williamson Voices for their vitally important work - at a time when it seems more important than ever.

I hope you have a very Happy Christmas when it comes.

Peter

[1]Williams, R. (2019). ‘What sweeter music’: issues in choral church music c.1960 to 2017, with special reference to the Christmas Eve carol service at King’s College Chapel, Cambridge and its new commissions. MA Thesis. York: The University of York. p. 100. [2] Harvey, J. (1984). Come, Holy Ghost. London: Faber Music. [3]Causton, R. (2016). Flight. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[4] Spitzer, R. (2015). Finding True Happiness. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. p. 67.

Comments